Black soldier fly larvae and tomato risotto. (Photo: Dezeen.).

Insects might just be the future of food.

As weird as that might sound, bear with me.

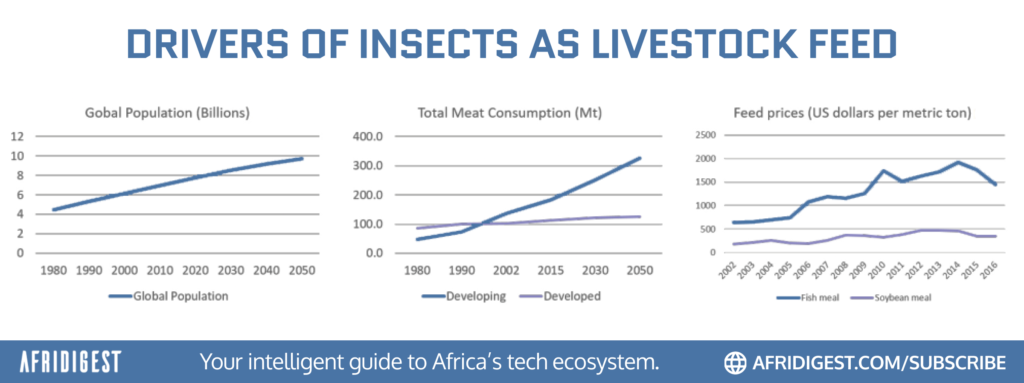

According to the latest UN projections, there’ll be 9.7 billion of us walking around by 2050. That’s a lot of mouths to feed.

And with meat consumption continuing to rise globally, meat production will have to basically double by 2050.

But producing meat is tough on the environment. And it’ll probably be a while before synthetic, plant-based or ‘fermentation-derived’ meat is truly mainstream.

But worldwide acceptance of alternative, non-synthetic proteins seems to be at an inflection point. Lab-grown, ‘cell-cultivated’ chicken was approved for sale in the US just a few weeks ago. And the EU approved a fourth insect for human consumption earlier this year.

Enter insect farming.

Farming insects consumes much fewer resources and has greater protein potential than farming meat — 100g of mealworm larvae, for example, offers 25g of protein, compared to 20g of protein in 100g of beef.

And even if you don’t have an appetite for arthropods, insect proteins can still improve the environmental footprint of your beloved burger indirectly — by replacing (or displacing some percentage of) traditional cattle feed.

And that’s not all.

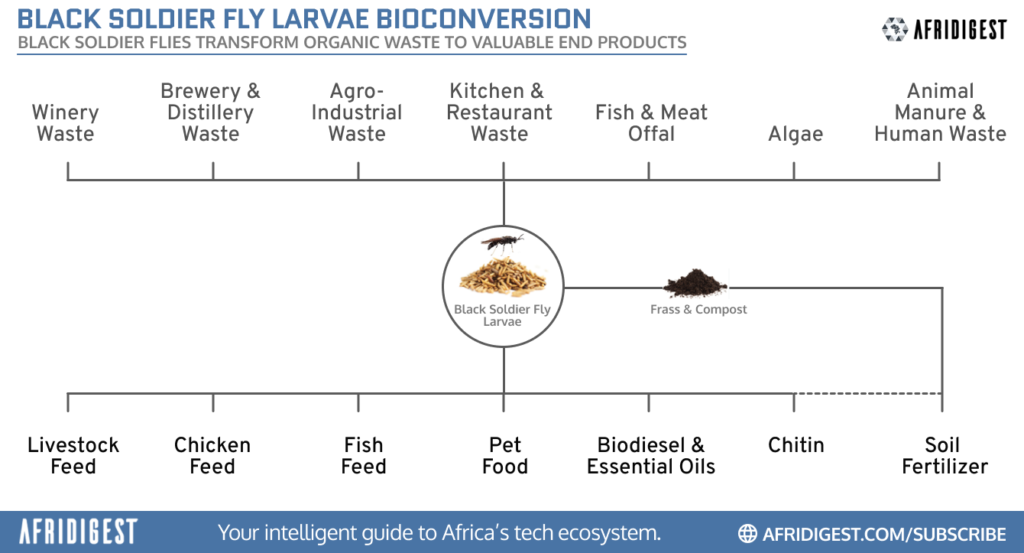

Certain insect species are natural ‘bioconverters’ — they efficiently transform organic waste into useful products.

And since organic waste accounts for over one-fifth of global methane emissions, that’s a pretty bug big deal.

Let’s take a deeper look at edible insects.

GLOSSARY

Entomophagy, from the Greek éntomon [insect] and phagein [to eat], meaning: "the human consumption of insects for food."

While entomophagy has just recently captured the West's attention, insects have always been a part of human diets. It’s estimated that roughly two billion people worldwide practice entomophagy today — with over 1,900 different insect species on the menu.

Bon appetit!

Food, feed, and finances

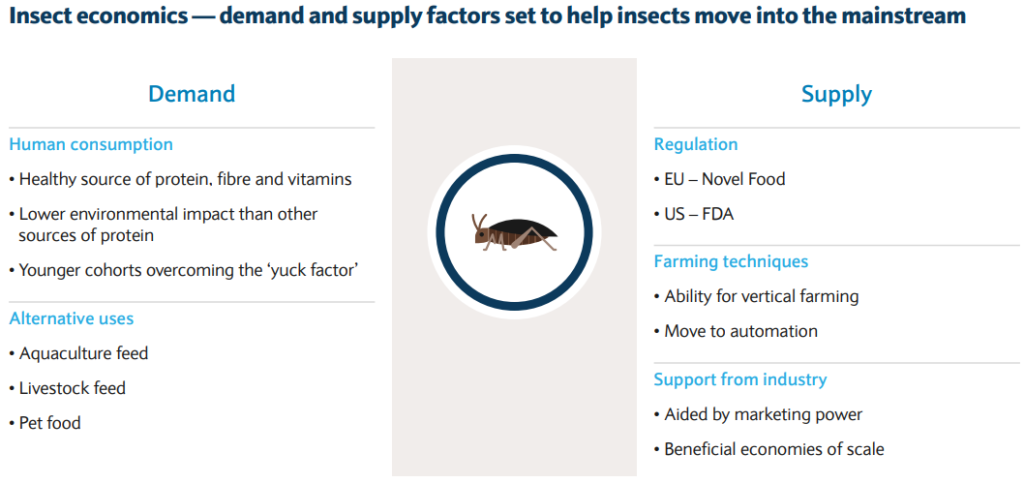

Slowly but surely, edible insects are moving into the mainstream — both for human consumption and animal nutrition.

Source: Food revolution (PDF). Barclays.

A number of different demand and supply factors are at play here, but large-scale insect farming in the near term is arguably driven by insects as feed, not as food.

Money talks — and rising costs of conventional animal feeds have created a sense of urgency. So there’s now more demand for insect-based animal feed than ever.

Fish and soybean meal are the top protein sources for animal feed, which makes up the bulk of meat production costs today.

Afridigestibles

574: Million metric tons’ worth of meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs consumed globally in 2020. (That’s roughly 75 kilograms per person FYI.)

60%–70%: Animal feed share of total livestock and poultry production costs.

$501.9B: Global animal feed market size in 2022.

4%: Projected global animal feed market CAGR through 2030.

$1.1B: Global insect feed market size in 2022.

12%: Projected global insect feed market CAGR through 2031.

70%: Consumer acceptance rate of insects as animal feed in Europe.

>85%: Acceptance rate of insect-based feed by farmers and feed producers in Kenya.

Africa’s top animal feed producers: South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Morocco, and Algeria.

>80%: Percent of worldwide insect farming activity focused on black soldier flies.

GLOSSARY

Polyphagous, from the Greek poly [many] and phagein [to eat], meaning (of an animal): "able to feed on various kinds of food."

One of the advantages of farming black soldier fly larvae is that they're polyphagous. They feed on a multitude of substrates — restaurant waste, fruits and vegetables, offal, brewery and winery byproducts, and even manure — turning them into beneficial ingredients.

Magic maggots

There are over 1 million different insects on the planet, but only a few are farmed industrially.

Crickets, mealworms, and locusts top the list for human consumption, but there’s just one star when it comes to insects as animal feed — Hermetia illucens, the black soldier fly.

Watch the ‘crown jewel’ of the insect farming industry work in this 2-minute video:

Unlike popular insect farming species like crickets and mealworms, black soldier fly larvae love organic waste and they practice polyphagy.

You can feed them spent grains from beermaking, all kinds of food waste, and even fecal sludge, and they still grow well. (They don’t eat bones though.)

In fact, that’s probably their superpower — an almost magical ability to convert organic waste into products that are valuable to us humans.

Even their poop frass is a nutrient-rich fertilizer.

“How is this insect so magical?” — Talash Huijbers, Founder & CEO of Kenya’s InsectiPro.

It’s no surprise then that up to 90% of insect farms worldwide focus on black soldier flies.

That includes South Africa’s Maltento. And here’s Dominic Malan, the company’s Co-founder and Commercial Director:

As an adult, it has no mouthparts [which is] important from a phytosanitary perspective…from a hygiene perspective. So, it’s a non-pathogenic fly and poses no risk from a pathogen transfer perspective.

But more importantly, because it has no mouth, what makes the larvae really interesting is the fact that they are almost designed to eat for their lives.

The little insect in larva form only lives for ten days. It hatches out as a tiny little neonate and for ten days it’s a larva and then it pupates, goes through metamorphosis, and hatches out as a fly.

This little larva can convert biomass into proteins and oils like no other organism.

The African outlook

Europe (and France, in particular) is the center of global insect farming activity today.

But the African continent might have unique advantages when it comes to black soldier flies: their larvae are most active at temperatures between 77 and 95°F (25-35°C). And that’s also the ideal range for adult fly mating and egg hatching.

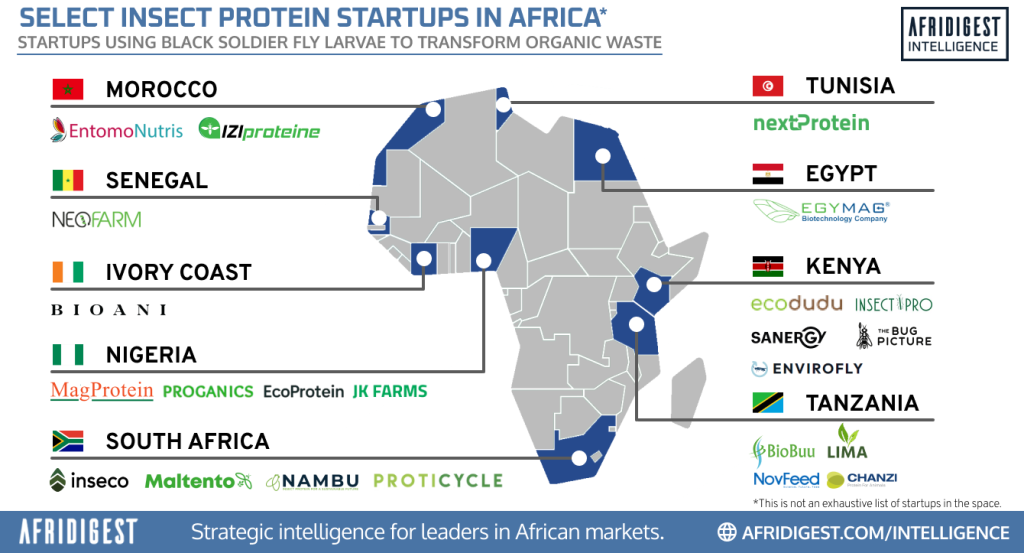

So black soldier fly farms across the continent can potentially spend less on infrastructure and overhead farming costs than their counterparts elsewhere. And with the right investments, partnerships, and training, there’s a real chance for Africa to become a global leader here.

Investors in Africa’s black soldier fly farming space today include Novastar Ventures, Kepple Africa Ventures, GIIG Africa, E Squared Investments, Futuregrowth Asset Management, E4E Africa, GreenTec Capital Partners, ShEquity, and others.

And here’s a look at some startups using black soldier flies to transform waste into various end products across Africa.

Expert insights

Founded in 2017, Nigeria’s MagProtein is quietly one of the largest insect protein producers on the continent.

Every day, it produces approximately 1 ton of dry protein, 3 tons of wet protein, and 6 tons of frass. The protein goes primarily to local fish farmers for feed and the frass goes primarily to local crop farmers for fertilizer.

That’s according to George Thorpe, MagProtein’s Managing Director.

I spoke with him to get a much-needed practitioner’s perspective.

Here’s the transcript — lightly edited for clarity:

What’s your perspective on the potential of insect protein production in Africa generally? Is it realistic to think that Africa can overtake Europe to become the global leader in this space?

“The most important thing to recognize is that the infrastructure requirements for scaling up insect production in Africa are much more advantageous than in Europe.

We’ve got the right climate, we’ve got the right cost structure, and we have access to tremendous waste.

Most of the waste in Africa is undervalued in my opinion, so there’s a lot of potential for upcycling of nutrients in this space.

And when we add the fact that 70 to 80% of protein products used for fish feed is imported in Nigeria & other countries, it’s clear that there’s a dire need for supply. This is a remarkable opportunity in a market-ready environment.”

Let’s talk more about access to waste. I’ve seen reports that some Kenyan insect protein producers get 80% of waste inputs for free. How does it work for MagProtein?

“We have to commend many of the food & beverage businesses producing in Nigeria, because they see the opportunities for synergy. Many of them have already done similar integrations in their value chain for plastics recycling initiatives and they see similar opportunities for organic waste circularity.

So, when companies like ours approach them and say, ‘we’d like to offtake a percentage of your waste because we want to use it to produce fertilizer that could help grow some of the inputs you need for your business,’ they see the synergy.

As a result, our access to inputs is probably more extensive than the players in Kenya that you mention.

Imagine a company making drinks that require hibiscus. Their outgrowers in, say, Jigawa require fertilizer. So it’s attractive when we say, ‘we don’t just take your free waste, we’ll also sell you or your outgrowers fertilizer on a long-term contract basis.’

Very simply, we partner directly with industrial-scale food and beverage companies across Nigeria to offtake their waste and in turn, we create a partnership that’s a complete circle.”

You mentioned that you sell mostly to local fish farmers & crop farmers. How do you think about the export market?

“There are always export opportunities. And it can be an attractive market. But the requirements are such that you generally need specific, global certifications that tend to require specific expertise. And here in Nigeria, where manufacturing is still a new science in my opinion, it can be difficult to have the same type of expertise.

At the same time, the local market is also very attractive. One of the drivers of insect-based fertilizer demand in northern Nigeria, for example, is that the soil is not as rich as it is in the south of the country, so farming requires organic fertilizer inputs. But the volume that’s available is very small and what is available is also very inefficient when compared to black soldier fly frass.

Similarly, the local market for insect-based protein is highly attractive. A lot of feed is imported which raises costs. So enabling farmers to access high-quality protein inputs within their price points locally creates tremendous demand and volumes for us.”

Recent black soldier fly fundraises in Africa

- South Africa’s Maltento raised $3.3M from Sand River Venture Capital in Week 24 2023.

- It also announced a $788K fundraise from DEG’s Up-Scaling program in Week 13 2023.

- Tanzania’s BioBuu raised a $200K seed round from the GIIG Africa Fund in Week 8 2023.

- South Africa’s Nambu Group raised an undisclosed seed round from E Squared Investments in Week 4 2023.

- Kenya’s Ecodudu raised $540K in a round led by Truvalu, with participation from GreenTec Capital Partners, ShEquity, and Opes-Lcef, in Week 51 2022.

- South Africa’s Inseco raised a $5.3M seed round led by Futuregrowth Asset Management, with participation from E4E Africa, Oak Drive Ventures, and others, in Week 17 2022.

Vectors of differentiation/specialization

- Inputs: Human fecal waste vs. other organic waste (generally)

- End products: Insect meal, insect powder, insect oil, frass, whole larvae, protein coatings, etc.

- Target consumers: Fisheries, meat producers, poultry farmers, pet food producers, crop farmers, etc.

- Target markets: Local, export

Moats & defensibility

- Access to raw materials in large quantities is an important factor. There’s no shortage of organic waste in Africa, but there are a limited number of large producers to offtake from.

- There’s also a technical aspect at play here as certain processes — climate control, automation, egg hatching, insect diet, vertical farming — seem to be closely-held secrets that require a fair amount of R&D. The requirements of precision black soldier fly farming weren’t generally known until this 2002 paper, and there’s still a lot of ongoing research. In other words, just twenty years ago, industrial black soldier fly cultivation didn’t exist, so the equipment and processes required for efficient large-scale production are still being optimized.

- Finally, scale matters. There are lots of low-tech, small-scale insect producers across the continent, but larger, tech-enabled commercial producers enjoy gains in unit cost and production yield/efficiency.

Share: